title-color:#FFF

background-color:#4699A8

Subtitle Above: Janji presents

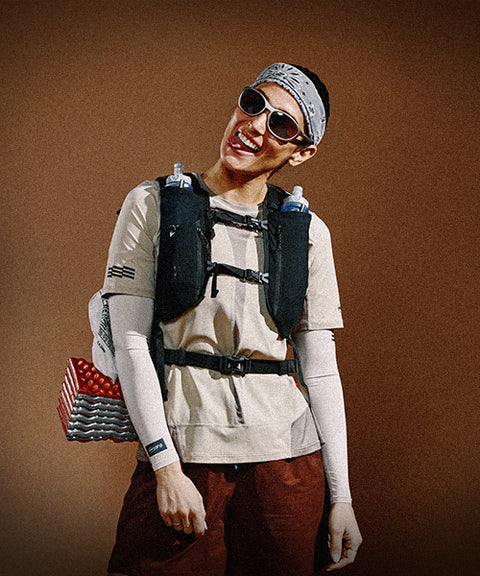

Subtitle Below: Featuring Eavan O'Neill

--END INTRO--

Photos + Video: Sam Rouda | Words: J. Travis Smith

"You can live a full, beautiful life with this condition, with this disability. You have a community around you that will be there to help you. And if you don't feel that you do, reach out to me."

As early as middle school, Eavan O'Neill remembers having issues with her vision. The center of her vision was blurry, and prescription glasses never seemed to help. Regular visits to her optometrist left her with more questions than answers.

Over the years, her vision continued to change, but no one knew why. Confused, she visited a specialist during the winter break of her senior year of college and received a diagnosis: Stargardt disease, a rare degenerative eye disease with no current treatment options. Her eyes were losing cone cells, causing blurriness in her central vision, and she would eventually go blind.

Feeling lost, Eavan began to run. She wasn't a runner in school, preferring soccer and lacrosse, but she laced up her shoes to remind herself that her body, if not her eyes, was still strong. Just a few years later, Eavan has become an activist, helping to provide the support she wished she had when she first received her diagnosis.

While running the 2023 Boston Marathon, she raised money for Mass Eye and Ear, the Boston-based team that helped guide her and her family through her unexpected diagnosis, and that continue to research promising clinical trials for treatment.

We recently sat down with Eavan to learn more about what it means to live with an "invisible" disability, how everyone can explore the world, and what the future holds.

Janji: Let's start in 2020. It's the pandemic. You're less than like a year past your diagnosis. Why did you decide to start running?

Eavan: I decided to start running because I felt super - for lack of a better word - lost and weak after I was diagnosed. Honestly, I felt sort of helpless and I think running for me, and I'm sure for others too, reminded me that I'm able bodied. I have my arms and my legs. I'm so grateful and lucky to have a body that's able to move and run and hike and bike and be in nature. I think running reminded me of that. It took something that made me feel weak and made me feel incredibly strong.

What do you hope to achieve through running?

What I'm trying to achieve through running and my partnership with Janji is hands down to spread awareness about Stargardt disease and other inherited forms of macular degeneration and blindness and bring nothing but positivity to it.

For me, when I was diagnosed, it was honestly like jumping off a cliff into no man's land. I didn't know anyone who had this. The support groups were really negative and I felt totally isolated. And I think that when I was diagnosed, I could have used someone like me to hold my hand a little and tell me that you can live a full life with this and still be the very best version of yourself, regardless of your disability.

I read that a big wakeup call for you was when you were with friends and mistook a street lamp for the moon. When did you first know that your vision was significantly deteriorated compared to other people?

Oh god, the street lamp. That quote went everywhere! I said that to a writer just off the cuff. It's funny because when I was first telling a friend about my diagnosis, she brought up that story and we were all dying laughing because it's just one of those things that you think back and you're like, 'Oh my God, I was so fucking blind.'

But that's a great question. I think I always knew I had bad vision from a very young age. My earliest memory of not being able to see was in sixth or seventh grade. I couldn't see through my lacrosse cage and my coach pulled my parents aside and said, 'I think she needs glasses.' But I never thought it was as bad as it was until moments where people were like, whoa, whoa, whoa that's a street lamp. That's not the moon.

I think when I really knew it was bad was junior year of college. I went to a very small liberal arts school and I would walk by people on campus and they would be like, 'Hey, Ev, what's up?' And I didn't know who they were. And that really started to scare me, when I wasn't recognizing faces of friends.

|

|

|

Congrats on completing the 2023 Boston Marathon! Can you speak a little bit about your experience in the race?

The race was amazing. It was one of the most incredible days of my life. And I knew it was going to be emotional because of everything that was tied to it for me. I fundraised for the hospital [Massachusetts Eye and Ear] that I love and believe in so much, it's where my doctors are and where I was diagnosed. That, coupled with the fact that it would be 26 miles through the city and neighboring towns where I live now, I knew it was going to be really special and emotional and really fun. And it was! It was an incredible experience. I hope to do it again next year and the year after. I mean, there's just no other marathon like it.

You didn't run with a guide this year. How was that?

It's not hard yet. I think it will become harder as I get older and this progresses, but right now I'm still able to run without a guide. It's pretty hard to explain Stargardt disease because there are some things you might think I'd be able to see that are so, so blurry. And then there are things that people are like, 'How did you see that?' So it's hard to explain. But with running, especially in a marathon where you have so many people to follow and you're not worried about cars or sidewalks or anything like that, it's a lot more doable. I don't know when the guide thing will come, but probably not for a little bit.

What do the next few years have in store for you?

That's a good question. I wish someone would tell me! I hope to just continue running and spreading awareness and being an activist in this space. It's funny, calling myself an activist. But I'd like to be someone that others can turn to. Even if they don't have a visual impairment, but rather anyone with a disability, especially people with invisible disabilities.

You look at me and I don't think you really would be able to tell that I'm blind. I don't have a cane. I don't have a seeing eye dog. And I know that there are other people out there that feel that way. So I just want to be a positive person that people can turn to when they need support or assistance. And also I want to show people that you can still be in the outdoors and still be active even when you have 20/200 vision like me.

|

“I went to a very small liberal arts school and I would walk by people on campus and they would be like, 'Hey, Ev, what's up?' And I didn't know who they were. And that really started to scare me, when I wasn't recognizing faces of friends.- Eavan |

|

Is there anything you wish you knew when you were diagnosed that you know now?

As cliché as it sounds, I wish I had known that everything's going to be okay. Because it's terrifying. There's no cure. Usually, when bad things happen in life, when you get hurt, for the most part there's some sort of cure or remedy. Well, I shouldn't say for most things, but for a lot of things. So finding out that you're losing your vision, especially at a young age (a lot of people with this disease are diagnosed even younger than I was) with no cure, it's really hard. But everything's going to be okay.

Like I said from in the beginning, you can live a full, beautiful life with this condition, with this disability. You have support around you and you have a community around you that will be there to help you. And if you don't feel that you do, reach out to me.

SHOP THE COLLECTION

Collection Grid

eavans-picks