Words by: Rickey Gates

Photography by: Rickey Gates, Bailey Newbrey, and Matt Shapiro

Packing List

It's not too bold of a statement to say that conversations about “classic trails” begin and end with the crossing of the Grand Canyon.

Completing the Rim to Rim to Rim (or R2R2R to the in crowd), stands as a lifetime achievement. It is biking L’alp Dehuez, climbing El Capitan, golfing Pebble Beach, swimming the English Channel… you get the point. While, with research and mindfulness, any given run can allow for a journey through time, no other run can compare to the textbook geological beauty of the Big Ditch.

I’ve lost track of the number of visits I’ve made to the Grand Canyon. It’s something that happens to you when you descend below the rim - there is the world above and there is the world below. You enter the canyon with anticipation and preparedness and leave with dream-like memories that can hardly be translated. The best we can do is to return again for a feeling that only otherworldly immensity can provide.

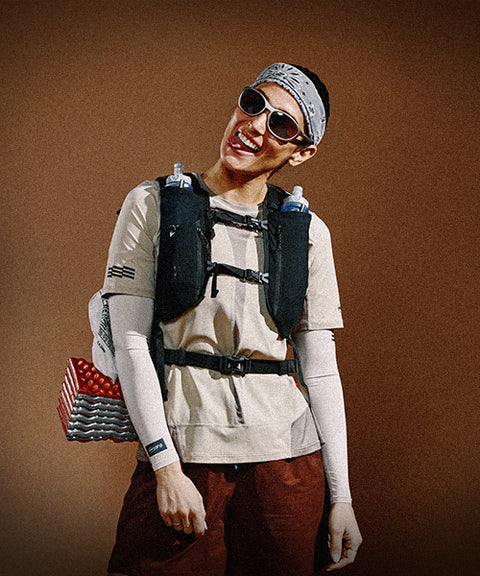

I gathered a small group of friends keen on a whirlwind trip from Santa Fe, New Mexico to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Though I brought a sleeping bag and pad, I knew it was unlikely that I would put them to use as we would either be running or driving. We left Santa Fe in the evening and arrived at the South Kaibab Trail at midnight. With late-May temps on the rise, we felt no need to hang out for long at the rim and by the light of a near-full moon began our descent.

I’d spend most of the next 44 miles with my Santa Fe doppelgänger, Bailey Newbrey (by height and weight, we are constantly mistaken for one another). Bailey is most known for his 2nd place finish in the legendary bike-packing event from Banff, Alberta to the US/Mexico border in New Mexico, which he did on a single speed.

Never fast but rarely boring - what can’t be seen, the mind invents. I set the pace, keeping it mellow. Among the common mistakes made in the Canyon is allowing oneself to enjoy the downward pull of gravity so much that before any climbing has begun, the knees are aching and quads are shot.

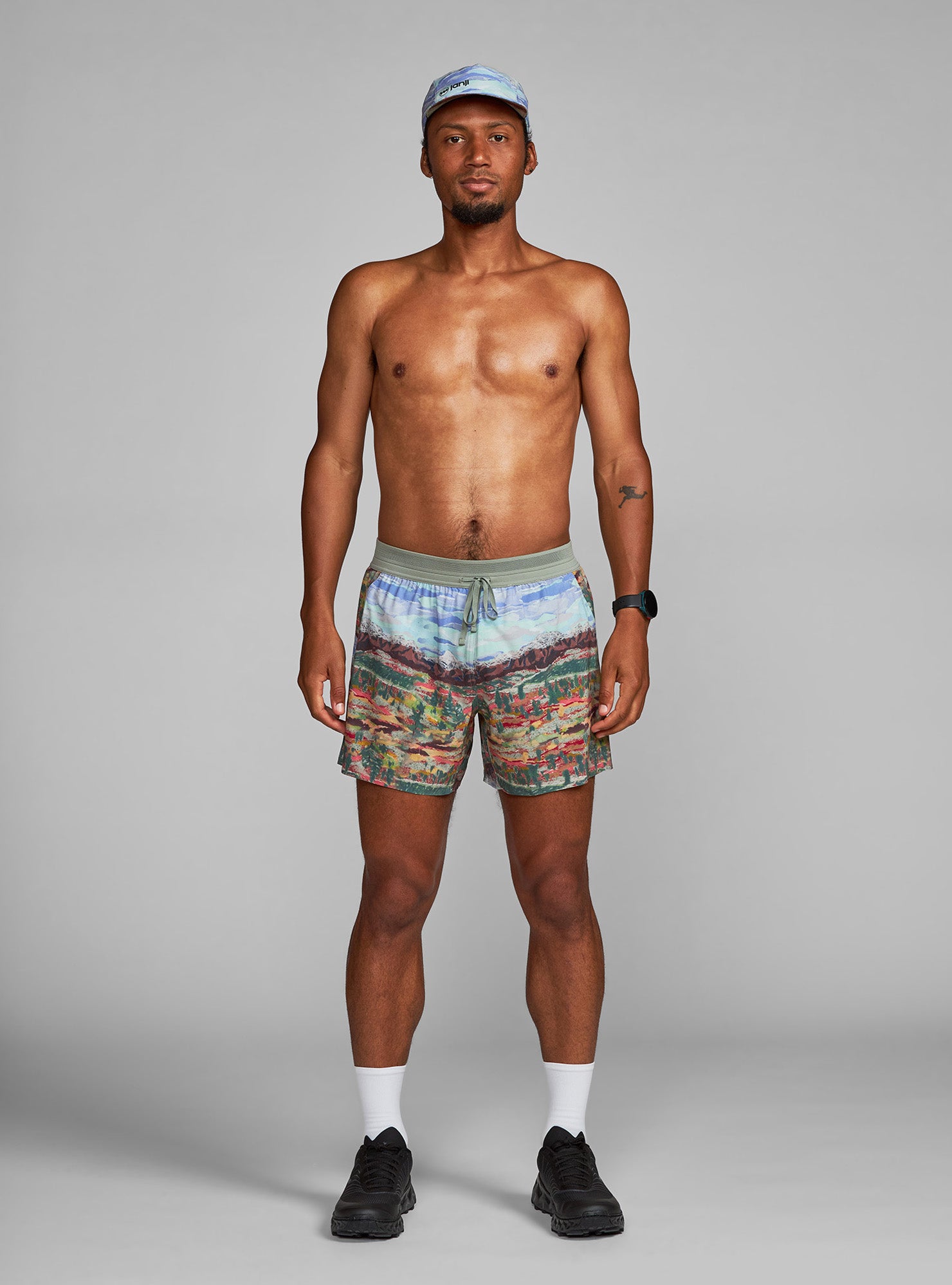

When dropping into the canyon, one is literally taking a journey back through time. In a vertical mile we sequentially passed through Kaibab, Toroweap, Coconino, Hermit, Esplanade - rock layers named like neighborhoods on a trip across town. The trail itself, a different journey back to a much more recent history of man’s attempt to conquer, or at least tame, nature. Following an hour and a half of descending, we entered the bedrock foundation of the canyon - a crepuscular layer of schist that seems to absorb light and give none of it back.

Here, in the basement of the Canyon, Phantom Ranch has served as respite from the harshness of its surroundings for over a century. If shade and water aren’t enough for you, beer, snacks and even ice are available to recharge you for the long journey out. At 2:30am, however, everybody around us was still asleep. We left three of our companions to join them, as Bailey and I continued on to the North Rim by the light of the moon.

The First Ascent

The North Kaibab Trail, from the river to the North Rim is nearly twice as long as its counterpart to the south. For the first six miles, the trail weaves along and over Bright Angel Creek, deep within the tributary gulch. The first birds started calling to each other well before sunrise - spotted towhees according to the app on my phone.

We passed through Cottonwood Campground where water abounds and, looking south behind us, we saw the San Francisco Peaks above Flagstaff, still covered in snow some 60-miles to the south. A couple more miles of gentle climbing brought us to Roaring Springs where a bathroom and water spigot gave us an excuse to pause, put away our headlamps and prepare for the final few miles to the North Rim.

The bulk of the climbing is done along this section of trail as you pass back through the obvious layers of rock: Esplanade, Hermit, Coconino, Toroweap and the welcomed greeting of the white Kaibab sandstone that tells you that you can’t ascend anymore unless you’re taken to climbing a tree. Given the south facing aspect and an additional thousand feet of elevation, the North Rim experiences a milder climate and a slightly different ecosystem than the South Rim. Aspen trees dip below the rim of the Canyon. Large game roam freely including a reintroduced herd of buffalo.

Halfway Done

After 22 miles and 6,000 feet of climbing we were over halfway through our day… on paper. But in reality, I believe that this is where the journey begins. Temperatures only rise throughout the day. The descent back to the river will abuse your quads in a way that is nearly impossible to prepare for and then of course, there’s the final ascent out of the Canyon.

Bailey and I commented on the chill in the air and on seeing our breath - a memory that we’d like to bring with us into what would soon become a furnace, as though the memory itself might cool us down just a bit.

We returned to Phantom Ranch to find one of our companions still sleeping, another resting below the shade of a sycamore tree and the third had already started up to avoid the midday heat, which we would soon be marching into.

After a cold lemonade and penning a couple of postcards to be packed out by mule, we continued on, across the Colorado River and back up through time on the South Kaibab trail, taking every chance to cool off in what little shade is provided by overhanging cliffs.

Difficulty-wise, Rickey rates the Grand Canyon's famous R2R2R a 7/10.

Trail History

Though the geological story of any given place is never simple, that of the Grand Canyon is as close to a children’s book as can be. The layers of rock that one passes through on the descent down to the river are laid out sequentially from the youngest Kaibab Limestone on the rim, deposited 270 million years ago, to the basement layer of Vishnu Schist found at the bottom of the Canyon dating back 1.7 billion years. Over time, a gentle (well, as gentle as plate tectonics can be) uplift of land raised the layers of rock to what is now known as the Colorado Plateau. The river found it’s way to where it is today seven million years ago which, on a geological timescale was practically yesterday. With the violent down-cutting of water and rock combined with the natural erosion of wind, freeze-thaw cycles and gravity, the Grand Canyon was formed.

Humans have been visiting the Grand Canyon for over 10,000 years, first for hunting and gathering purposes followed by farming where land and water would allow. For hundreds of years, Navajo, Southern Paiute, Hulapai, Hopi, Zuni and Apache communities have lived near the Grand Canyon and consider it a sacred place. Today, only the Havasupai still call the Grand Canyon home.

The more modern history of the Grand Canyon begins with the harrowing descent down the Colorado River in wooden dories by Civil War veteran, John Wesley Powell and a team of men. A generation later, seeing the potential for tourist revenue, the first modern trails were built first from the South Rim and then the North Rim.

In 1921 a suspension bridge was built across the river allowing greater access to both sides of the Canyon. That same year, a stunt rider, Bonnie Gray, claimed a single crossing of the canyon took her 6:25, a feat she believed “will never be equaled by a woman.”

A decade later, with the help of the Civilian Conservation Corp, the trail was drastically improved to its current condition - double wide in most parts. Thanks to its runnable condition and to the running boom of the 1970’s, a sanctioned race across the canyon emerged in 1978 followed three years later by an official double crossing. The race had t-shirts, sponsors for the participants which numbered in the hundreds before it was shut down by the National Park Service in 1982.

For the past 40+ years, the crossing and double crossing (and quadruple, etc) of the Grand Canyon has thrived as a personal experience separate from races. With its history and grandeur, it stands alone as a test of fitness and grit.

Getting There

The Rim to Rim to Rim can be done starting at the North Rim or the South Rim, however, most people choose to go from the South Rim due to its proximity to Flagstaff and more ample access to supplies. The North Rim, it should be noted, is closed through the winter months. Check the National Park Service website before setting out.

On the Day

Descending into the Canyon, regardless of fitness, should not be taken lightly. Since records have been kept, it is estimated that nearly 100 people have died in the Grand Canyon due to dehydration. Countless rescues happen every year - ill-prepared hikers and runners. Don’t be a statistic! Do your research, know your skills and come prepared.

Only feel like going across one direction? Or, having made it across one way but feel like a second crossing might be dangerous, two shuttles per day are provided by the park.

Run with Rickey

Feeling inspired? Sign up to join Rickey on his next big trail-running trip.

About Rickey

For the past thirty years, running has been a central part of Rickey Gates’s life. Whether it be in the competitive realm of racing or the obsessive realm of curiosity, or a mindful space of meditation, running has long been the primary medium through which Rickey has interacted with the broader environment around him.

In an effort to understand his country, community, and self, Rickey completed two unbelievably ambitious, back-to-back running projects: TransAmericana (2017) in which he ran across the entire United States, and Every Single Street (2018) in which he ran, street by street, the entirety of San Francisco. His current obsession (which you are currently reading) is to paint a picture of North America through trails. He lives in Santa Fe with his wife and two children.