title-color:#000

background-color:#F3F3F3

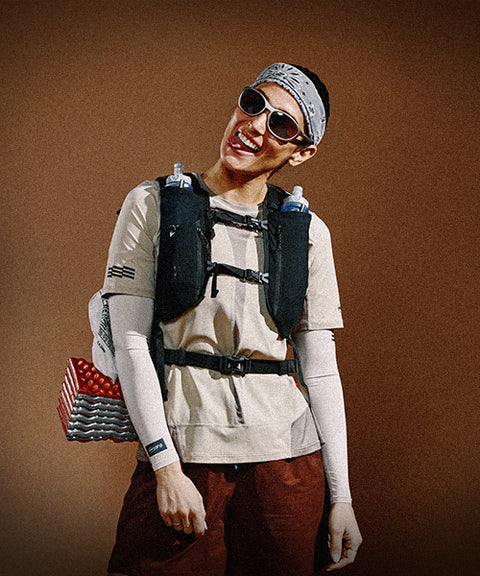

Subtitle Above: MORGAN SJOGREN

Subtitle Below: NOTES FROM THE FIELD

--BEGIN CREDITS--

DATE

June 22, 2021

CREDITS

Stephen Eginoire, photographer

WORDS

Morgan Sjogren

RUNNERS

Morgan Sjogren

--END CREDITS--

Janji Field Team Member Morgan Sjogren Follows Her H2O in the American Southwest

Morgan and her partner recently went on a “water run” through their backyard in the American Southwest to prepare for an upcoming hike. Finding water is not something you can rely on when adventuring in the desert; although water sources, like Lake Powell, may be visible, they are far too often inaccessible. Morgan details her experience water caching, or hiding water at specific locations along her route, to decrease the amount she needs to carry.

Read about Morgan's water run below and then join Morgan and runners across the globe to Follow the H2O.

--END INTRO--

Water Run

By Morgan Sjogren

|

During every run in the desert, water is the defining factor. Your mileage or destination objectives are obsolete if you cannot either find water along the route or carry enough to get you there and back. Access to any water could be many days apart. The recommended dose of H2O is one gallon (four liters) per person per day. Each gallon weighs 8.34 pounds. Even on shorter desert runs I always travel with close to this amount of water, as it could be the difference between life or death if I get injured, delayed, or lost. Traveling “fast and light” across the desert means carrying a minimum of eight pounds. Although I wish to travel long distances and explore the desert’s secrets, on each and every run my focus is not on my watch nor destination, but on how much water I can carry and how much I can find. |

|

|

Nestled in southeastern Utah between the San Juan River and Lake Powell, the Glen Canyon backcountry is about as barren as it gets. There are no flowing streams, nor reliable springs or seeps in this sprawl of sand and stone stretching between the two waterways. This landscape is set atop a plateau bordered by sheer cliffs that tower hundreds of feet above Lake Powell, was once a beautiful Colorado river corridor before the Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1963. |

“It’s mind-bending to think that out here running towards the source of my water means that I am not able to access it most of the time. Meanwhile, there are folks hundreds of miles away in Phoenix and San Diego literally drinking the water I can see but cannot reach!"

|

The same applies to residents of the nearby Navajo Nation, also visible on the other side of the untouchable waterways surrounding me. Despite living so near to the source of water that helps cities flourish around the arid west, 30% of homes in the Navajo Nation do not have access to running water. For anyone removed from the luxuries of running water, accessing and finding water are a central focus of life. Though challenging, the act of running in such a dry place is a privilege and a choice compared to those who face the struggle in their everyday life. |

|

My “water run” route did not follow a designated trail, nor did it contain any guaranteed water sources like springs or streams. The path I followed was dictated by the contours of the landscape (steep hills mean “go!” and cliffs mean “no!”. Yet, finding enough water just to safely take a look at Lake Powell will be the ironic crux of this journey. Running between the sand and the slickrock ramps brings my feet in contact with a landscape shaped by wind and water for millennia. The wind howled incessantly, making it possible for me to imagine at least half of this creation process. As I climbed up the orange-colored domes I searched for potholes eroded into the smooth Navajo sandstone. These natural bowls hold water after storms and are the best place to find water in this landscape--if you’re lucky. Despite a massive storm the week before, to my dismay even the deepest pits were bone dry.

“The desert does everything to remind humans that they are not in charge around here--nor does it care whether you make it out alive."

Though it was sunny, storm clouds rolled in. Desert weather is tempestuous, and the swirling winds made it impossible for me to predict what it might do next, so I pulled my windbreaker out of my pack and put it on as the dark clouds blanketing the sky. Though a burst of rain could potentially fill some potholes on the slickrock with clean water, certain areas of the desert, like canyons and washes, can siphon water from storms into deadly flash floods. So I headed to higher ground even though it made me feel like I was reaching directly for the storm. The desert does everything to remind humans that they are not in charge around here--nor does it care whether you make it out alive. Finally, the sky unleashed, but there was no water, and instead, a storm of sand consumed us. Yet another reminder of the desert’s cruel whims.

|

The next morning as the sun climbed above the sea of sandstone we accepted reality--the only water we could be certain of would be water that we carried ourselves. However, the proposed route around this particular stretch of the desert might take me upwards of ten days. At one gallon of water per day per person, it would be impossible to carry even half of this. To make it possible, Steve and I needed to carry as much water as we could fit in our packs, and then hike it out to cache in a hiding spot for later this spring. |

|

Heading into the opposite direction of yesterday’s run felt daunting and invigorating, as we did not know what lay ahead of us. I suppose that’s the appeal of doing something like this--the spirit of adventure and exploration. Even with a heavy pack, the miles slipped behind us like a dream as the wondrous and strange terrain of the desert, ridgelines of creamy colored sandstone and powder-fine orange sand dunes, hypnotized us onward. The scenery distracted us so much, that at one point we veered off our route. Using landmarks and our maps we aimed back towards our landmarks, a detour that added an hour of hiking but immersed us deeper into this remote and wild place. |

|

“Please do not disturb or we will DIE!!!"

Three hours later we reached a critical junction that the spring expedition route will cross two-times, making it an ideal spot to place our emergency water rations. We pulled all but one liter of water out of our packs and blessed it by writing important notes across each container:

“Please do not disturb or we will DIE!!!”

With the water tucked out of sight, we gave it one last glance, turned around, and started the long walk back. My pack now almost weightless, I smiled as I thought about how absurd today’s hike was. Leaving water behind in the desert, saving something so precious for another day, is the ultimate act of faith. In a few month’s time we’ll be back here at this water cache, ready once again to carry heavy packs and walk through the desert in search of water, and in turn, quench our insatiable thirst to explore in the desert we so dearly love.